Exploring Shading Algorithms through Ray Tracing

Ray tracing has long stood as one of the most principled approaches to rendering, precisely because it models light transport in a way that is both mathematically grounded and (in my opinion) conceptually elegant. My primary aim in implementing these was to develop a working understanding of several shading algorithms, as well as create find the satisfaction of creating fun images. :)

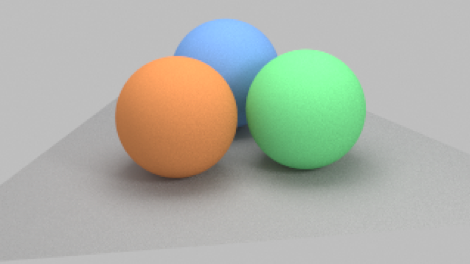

All images presented here were generated with 160 samples per pixel, which balances image quality with computational tractability.

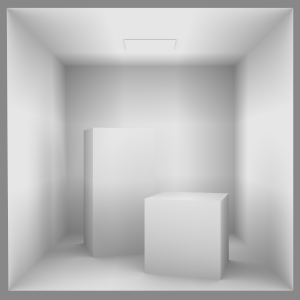

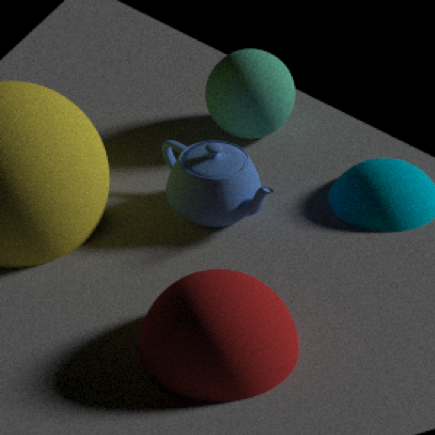

Ambient Occlusion

Ambient occlusion is often introduced as a baseline shading model. It does not attempt to simulate global light transport, but instead estimates the relative accessibility of a point on a surface to ambient light. The algorithm proceeds by sampling rays in a hemisphere oriented around the surface normal and determining whether they intersect other geometry. Points with more blocked rays appear darker; those with fewer appear lighter.

This yields images that highlight crevices and occluded regions, producing a sense of depth and structure even in the absence of direct light sources. While not physically accurate, it is computationally inexpensive and serves as a useful starting point for understanding how stochastic sampling can capture subtle spatial effects.

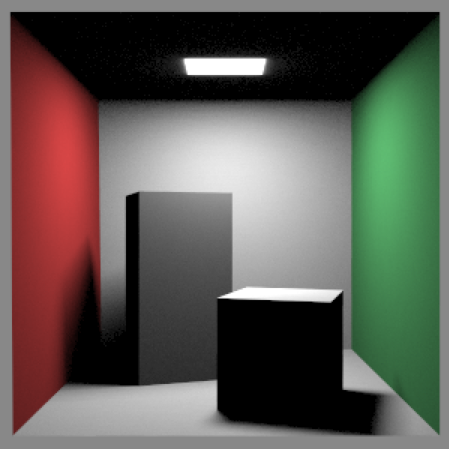

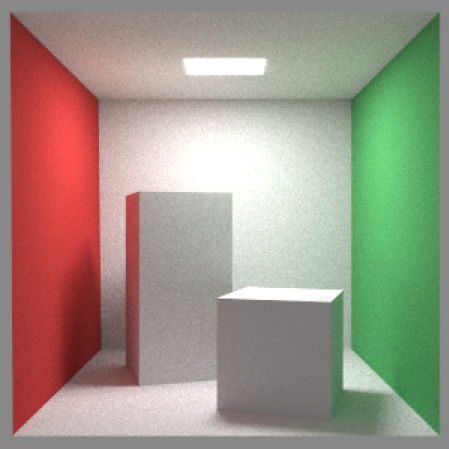

Direct Illumination

The next step was to extend the renderer to account explicitly for direct illumination using Monte Carlo sampling. Here, rays are traced from the camera into the scene, and at the first surface intersection, secondary rays are sampled toward the light sources. The contribution of each light is weighted according to the bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) and the visibility term (i.e., whether the light is occluded).

This method captures shadows and shading that are more faithful to physical reality than ambient occlusion, but it is still limited. Because only direct light paths are considered, interreflections and indirect light transport are absent. Nonetheless, it illustrates clearly how Monte Carlo integration can be applied to rendering and how sample count directly impacts noise and convergence.

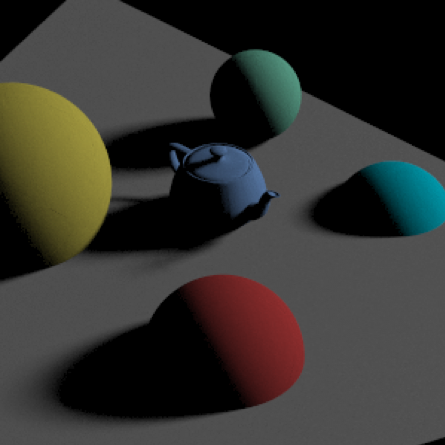

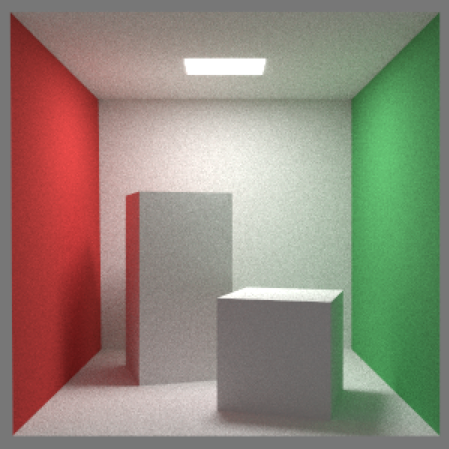

Global Illumination

To capture the contribution of indirect lighting, I implemented a recursive global illumination algorithm. At each surface intersection, rays are stochastically sampled according to the surface BRDF, and their contributions are accumulated. In practice, this amounts to tracing light paths that may bounce multiple times before reaching a light source.

The recursion terminates at a fixed maximum depth—in this case, five bounces. This choice represents a compromise: allowing sufficient depth to capture multiple interreflections while preventing exponential growth in computation time. Even with this constraint, the results illustrate a qualitative leap: diffuse color bleeding, soft interreflections, and a much greater sense of realism.

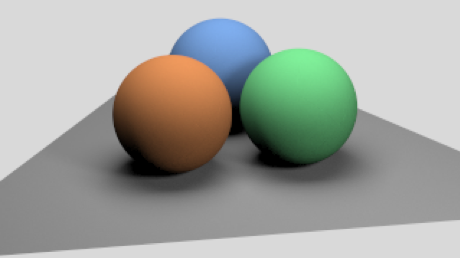

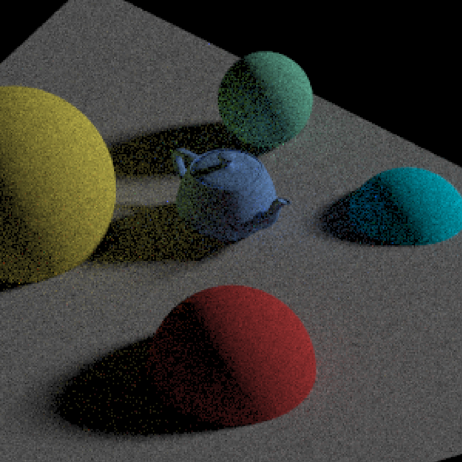

Global Illumination with Russian Roulette

One limitation of the fixed-depth approach is that it treats all paths equally, regardless of their actual contribution to the final image. Rays that continue bouncing may in fact add negligible energy, yet they consume computation. To address this, I implemented Russian Roulette path termination.

With this method, at each bounce a ray is terminated probabilistically based on a survival probability (here, 0.25). Paths that are terminated contribute nothing further, while those that survive have their contributions scaled appropriately to maintain unbiasedness. This reduces wasted computation and better aligns the algorithm with Monte Carlo principles, since expected contribution rather than deterministic depth governs continuation.

Some Thoughts

Noise and convergence: Increasing sample counts improves image quality, but diminishing returns set in quickly. Understanding variance reduction is essential to making Monte Carlo methods practical. Termination strategies: Comparing hard cut-offs to Russian Roulette illustrated how algorithmic choices can directly influence both efficiency (obviously) and realism (less obvious).

Implementing these renderers sequentially revealed to me how successive algorithmic refinements bring rendered images closer to physical plausibility. Each method carries trade-offs between complexity, computational demand, and visual fidelity, and seeing those differences manifest in my implementations was nice to see and definitely deepened my appreciation for both the mathematical underpinnings and the practical challenges of photorealistic rendering.